How customers justify avoiding you

People avoid information more when they are given a reason to let themselves off the hook.

That’s the key takeaway from some fresh research from Woolley and Risen (2021) called “Hiding from the truth: When and How Cover Enables Information Avoidance”.

There are key implications from both a business and personal perspective resulting from this finding.

Let’s talk business first.

How you talk to a customer about product features is either going to help them justify their decision to buy or help them avoid you entirely.

What should you, or should you not, tell them, then?

Information Avoidance

Information Avoidance is our tendency to avoid information we don’t want to deal with, like calorie labels on menus, ethical practices related to a product we want to buy and booking medical appointments.

The tricky thing is that customers may tell you they want certain information (or regulators may demand it), but it actually reduces their propensity to buy. The information creates conflict between their “should do” and “want to” selves.

“I should want calorie information on the menu, but it makes me feel bad because I want to eat the burger”, for example.

I tend to think of Information Avoidance as the flip side of Confirmation Bias. Where Confirmation Bias is our tendency to seek-out information that affirms what we know or believe, Information Avoidance protects us from that which causes us discomfort. Both interfere with our ability to make rational decisions but make rationalising our decisions all the easier!

In thinking about consumers, Woolley and Risen hypothesised that when people were able to justify their decision without having to acknowledge they were avoiding information, they would be more likely to ignore it. In essence, finding a comfortable way to let themselves off the hook.

Providing a Cover Story

In the language of this study, the consumers were provided “cover”, which meant being able to “attribute their choice to another relevant feature in the environment (e.g., another product attribute) rather than to the real reason for their choice. In other words, cover provides consumers with an alternative justification for their decision.” It’s like a cover story we can tell ourselves and others to explain an awkwardness away.

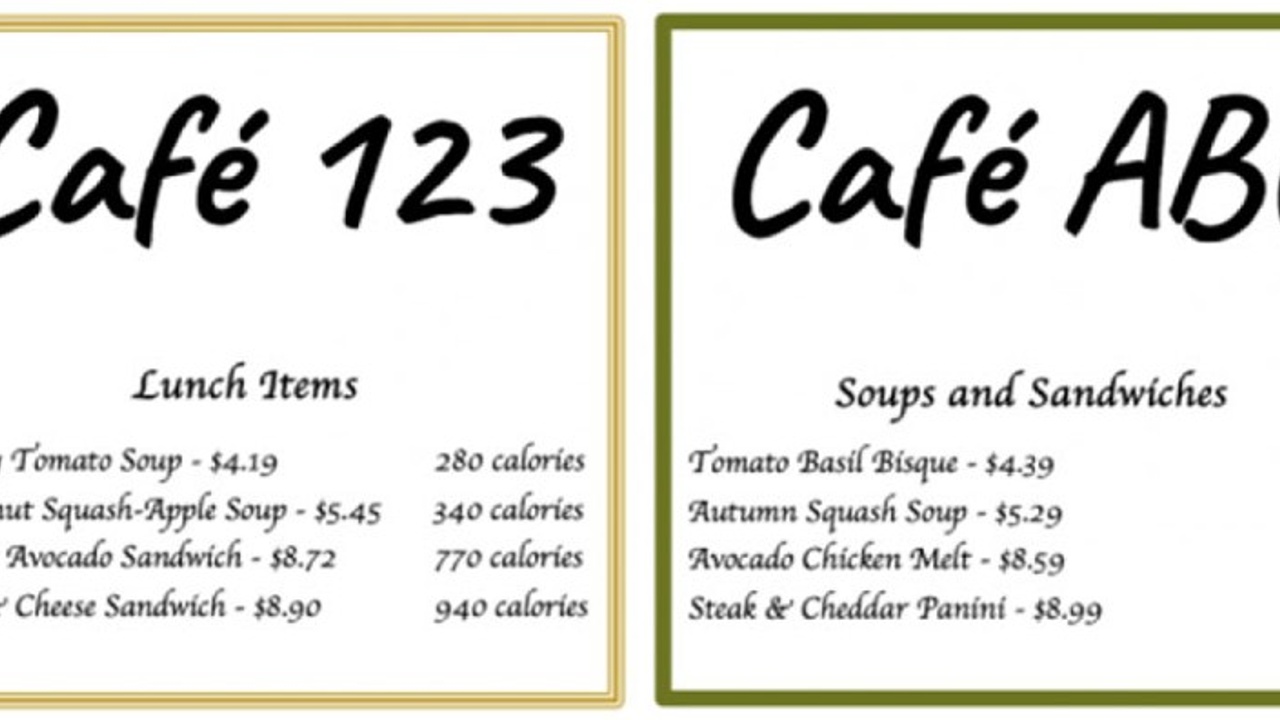

In the first of seven studies, online participants were shown menus for two cafes and asked to which they preferred to go. They received a small gift-card for that café, so their decision had real world stakes.

Café 123’s menu (on the left) included caloric information, but Café ABC’s did not.

Along with the menu, participants either got additional information that was exactly the same between the cafes (“no-cover condition” on the right) or information that gave different ratings for service and atmosphere (“cover condition”).

So, the question was, when people were given an “out” to avoid the menu with calories, did this change their decision?

Yes. More people chose Café ABC, the menu without calorie information, when they had a justifiable reason to avoid Café 123 than when there was no cover provided (43.5% vs. 32.8%). With real money on the line, providing “cover” increased information avoidance.

The researchers replicated this finding through a total of seven studies, testing climate messages on water bottles, food labelling, UV photo (skin damage) avoidance and public vs. private decisions (where it was determined it is more about justifying to the self than others). In sum, they estimate providing cover increases information avoidance by more than 13%.

According to the researchers, “more people avoided information they were conflicted about receiving when they could attribute avoidance to another (relevant) feature of the choice than when they could not.”

When people experience conflict between what they want to do and what they should do, they are more likely to seek and use cover to justify their want.

What this means for you in business

If you are selling a “should do” (e.g. insurance, tax services, health products that require self-discipline or sacrifice)

- If you include information people might like to avoid and provide cover for them (i.e. additional features or ratings) that your competitors do not, they are likely to prefer your competitor. If you are selling bottled water and include water conservation messages on your label but other bottles do not, people are going to be more likely to avoid you and buy from your competitor, for example.

- Destigmatise “bad” news. Don’t go heavy on scary, finger-pointy, ‘thou shalt’ messages.

- Divorce the information from the product, providing cover so they don’t feel bad about avoiding it and instead see it as separate to the product itself. Examples include Product Disclosure Statements (PDS) used by financial institutions, Terms and Conditions for software and calorie information positioned before the food label.

- Explicitly raising the tendency to avoid information has been found to reduce the likelihood they will. A comment like “I know we don’t like to talk about this but…” might work wonders.

- If you do not have to provide information that people might like to avoid, don’t!

If you are selling a “want to” (e.g. indulgent food or services, holidays)

- People are seeking reasons to justify their “want” over their “should” and will endeavour to avoid information that makes them question their decision. Make it easy for them to choose you by eliminating or deprioritising unappealing information (like ABC’s calorie-free menu).

- If you need to include unappealing information (like Café 123), don’t provide cover because that will encourage them to avoid you.

What this means for you in your personal life

Enough about business, right? You and I are consumers too, battling the “should do-want to” intrapersonal debate on a daily basis. Lessons for us:

- We are wired to avoid information that causes us discomfort

- We gravitate to choices that mute any icky sense of dissonance i.e. providing a cover story to fit nicely in our narrative about what a good person we are

- If you want to do more “should do’s”, take the pressure off yourself to engage with the information. Better to take an easy first step (e.g. a fun quiz, an initial consult) rather than forcing yourself to get into the detail.

- If you want to do less “want-to’s”, acknowledging the tendency to avoid information and to seek any justification to indulge will magically help you counteract this proclivity.

It’s fair to say this research has really got me thinking about how people justify decisions. Today we’ve talked a little about how people justify things to themselves. Look out for future posts that deal with helping your customer justify decisions to other people.

You might also find interesting:

To get articles like this delivered straight to your inbox every two weeks consider subscribing today.